It is financially beneficial to Pharmaceutical companies to publish all their data

I’ve been reading a book by Ben Goldacre called Bad Pharma. It’s interesting to me for several reasons. Firstly it is about scientific method through data analysis (something I always actively promote on this blog), secondly I did a degree in Chemistry (effectively the forerunner to drug manufacturing) and thirdly I work for a company that deals with a large number of pharmaceutical clients. I’ve also seen Ben live on the uncaged monkeys tour that he did with a number of comedians.

Ben argues that one of the main problems with the industry is that data is suppressed about the effectiveness of drugs and their side effects. This seriously impacts a doctor’s ability to prescribe the right drug and means that patients’ health is seriously effected. Half the book is about how ‘Marketers’ then use this data in ways that they should, but I’m going to ignore that. If you’re on this blog you’re probably not questioning whether marketing is evil or not (and most of what he complains about isn’t marketing, it is sales).

I’m going to argue in this post that suppressing data is bad for pharmaceutical companies.

But first some maths lessons. I’ve talked about sampling data before and I’ve talked about the difference between accuracy and precision.

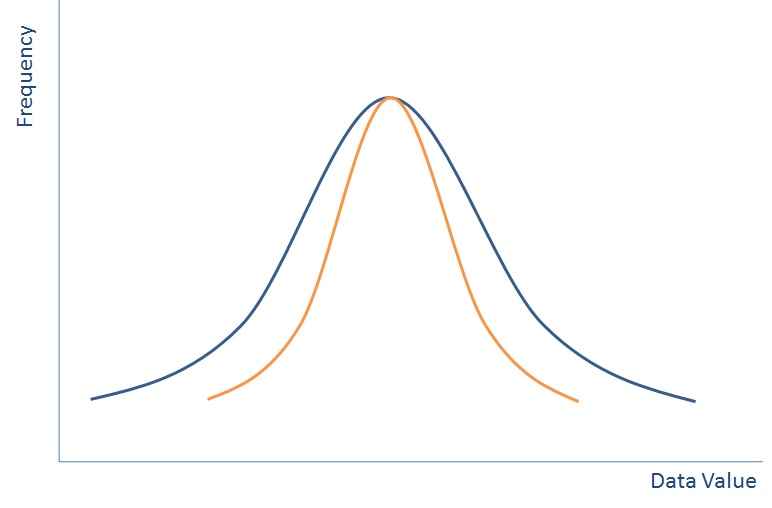

Data is best represented when put in a distribution like the one above (this isn’t the only way that data can be distributed, but is called the Normal Distribution because is it one of the most common). If you plotted everyone in the world’s height on a graph then it would like the blue line above.

With a distribution like this if you pick someone at random then they are most likely to be in the middle, but could be near the outside. By picking one person, you may not pick a very indicative view of all of the population. So we do what we call sampling.

If we group all people completely randomly into groups of ten and then plot the average height of each group of ten people then we’ll end up with a normal distribution again – something that looks a bit like the orange line on the graph above – the spread will be much lower as each group of ten is less likely to have outliers, but the average should still be in the same place.

If you group everyone into bigger sample sizes then it turns out that your distribution gets closer and closer to the average until eventually your sample size is everyone and it is just a line in the middle.

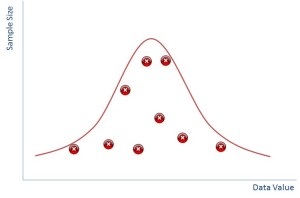

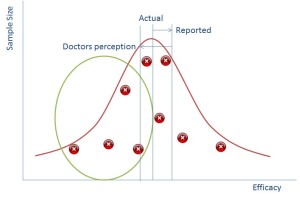

It turns out that if you plot sample size against your data value then it also produces a normal distribution. The bigger your sample size the less likely you are to see outliers and the smaller samples sizes will have more outliers.

In reality of course you don’t ever do hundreds of samples, you would do a few and you might end up with a distribution that is just the red crosses in the diagram above whereby you have to ‘guess’ where the distribution is.

This is effectively how randomised drug trials (should) work. A pharmaceutical company will run a number of trials, usually some small ones to start with and they’ll monitor its effect either against a placebo (this is becoming less common) or against their nearest competitor. They then provide this information to the regulators who approve or not their drug to be used in relation to what it was you’ve been testing it against.

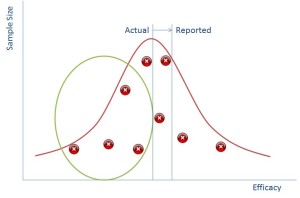

Except it isn’t quite that simple. It’s relatively expensive to get a drug to this point of the market and having it not approved for use would result in a lot of money lost (hundreds of millions of pounds). So the drug companies cheat. They suppress evidence that shows that the drug isn’t effective in a number of ways (read Ben’s book to find out how!).

So if we can suppress the data in the green circle we can make it seem to the regulator that the reported impact of the drug is much better than it actually is (and this works vice versa for side effects).

As an aside, The Cochrane Collaboration (no relation, I’m afraid) have come along and said well rather than putting these points on a graph, it is far better for doctors to be able to see their data in a better fashion. Rather than having each of the points as a separate report, it makes more sense to add them all together to give one really big sample. They do this in ‘blobbograms’ that are the output of systematic reviews and is a great visualisation technique.

So why is this all relevant now? Well the simple truth is that in the past pharmaceutical reps would go to doctors with a couple of studies representing the points above and use that as a way of persuading doctors to use their drugs. Now, however we have the internet and doctors go and look on that. The information is all there and doctors are more likely to be able to tell that there is missing data because they’ll see the gap from the green bubble.

What does this mean? It means that a doctor’s perception in an online world of how good your drug is, is probably lower than it actually is.

Let me put this in simple terms:

Fewer doctors will prescribe your drug if you suppress data.

Of course this is all fantasy at the moment. Because every pharmaceutical company suppresses data we know that all drugs are perceived as less effective than they really are and so it is almost impossible to work out which one you subscribe.

But this will change. One pharmaceutical company will reveal all their data at launch and it will be spectacularly profitable forcing all pharmaceutical companies to follow. If you think this won’t happen, you will be last and your drugs won’t be used.

In an online world where data is accessible, doctors can very easily find out data about various different drugs for the same illness potentially whilst the patient is sitting in front of them. The one that looks like it is hiding the least will win.

Therefore, my assertion is that whilst Ben Goldacre argues that it is better for doctors and patients if drug companies don’t suppress data, I think that it is better for pharmaceutical companies as well.

Now all we need to do is persuade the Regulators that it is ok to approve drugs that may not appear to be as effective as other drugs that are already on the market.

Leave a Reply